CHIPs

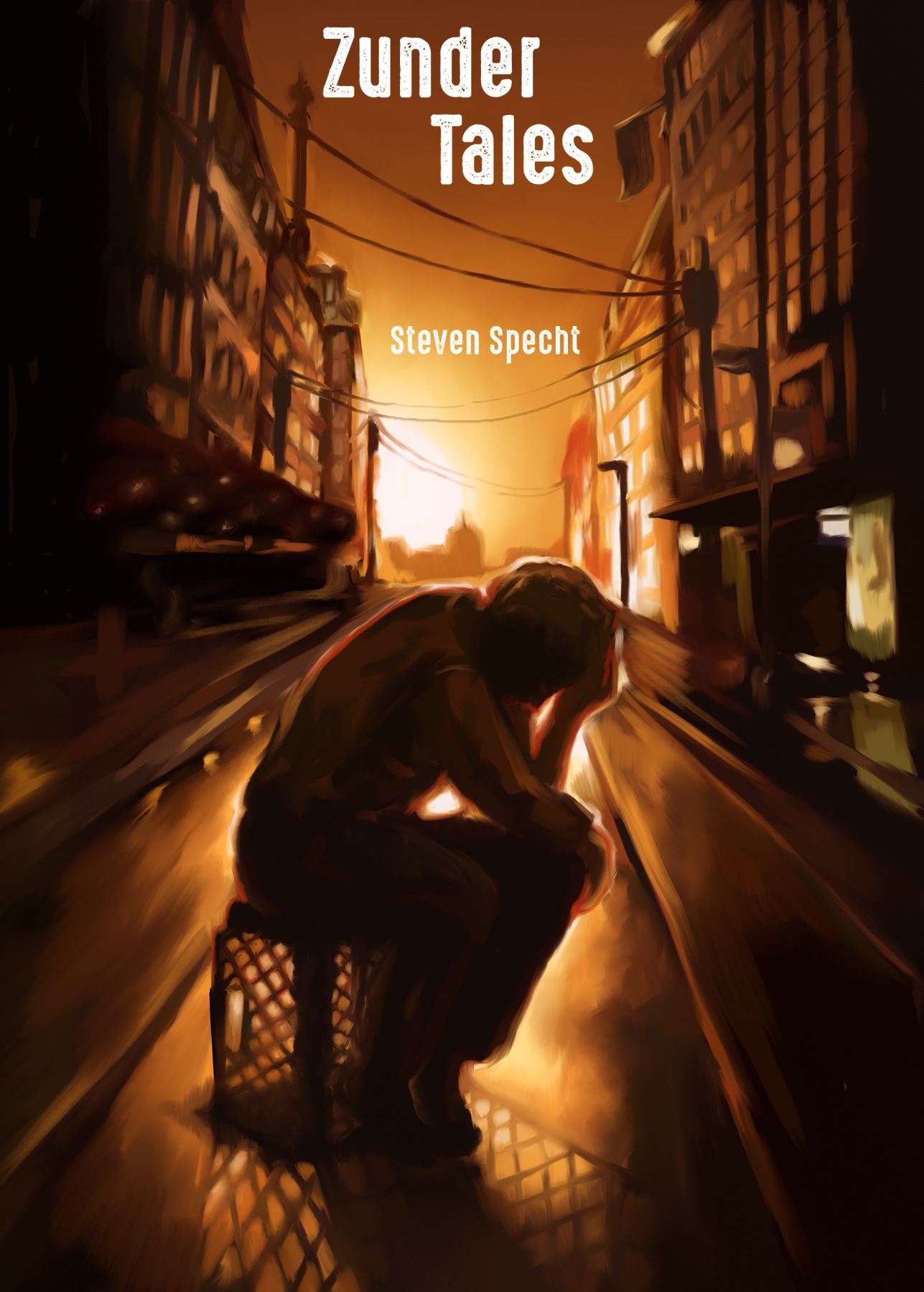

This is an excerpt from a collection of short stories titled Zunder Tales

If you like this story, please consider buying the collection in the link at the end of the story.

CHIPs

Obidiah woke instantly in his sixth-floor hide. His jolting alertness felt no better after 82 years than it had when he first received the implant at the base of his brainstem. A low-level voltage zapped the nervous system, causing every neuron to fire simultaneously. Consciousness came in a flash of light at precisely 0645. The current wasn’t painful, just one of those odd sensations that defy description, like grabbing a live wire or having a doc plunge out the urethra with a Q-tip after a night of questionable decisions.

Sleeping in wasn’t an option but neither was oversleeping—so a small blessing. He only needed one hour of sleep a day and it could be induced and ended at a precise time. The 0645 rise-and-shine setting every day was the last thing he’d been able to do before his personal remote had fallen apart. The remote hadn’t been designed with the intent of working for decades on end, but few had ever been involved with the program. When the purges came scientists were some of the first to get rounded up. He was on his own. He had not realized the gravity of the decision to set an alarm that would result in sleeping and waking up at the exact time every day for the rest of his life. He rolled over quietly in the hide conscious of the noise; making rustling noises echo down the corridors of an old public housing complex he’d used for shelter the last three days. The respite from being on the move was deserved, but he was a day’s walk from his makeshift laboratory and he could not resume work until the Penitents left the area.

They’d been working over a guy for three days, and the scent of seared flesh wafted up from the courtyard. Obidiah grew disgusted, not with what they had done to the poor bastard, but for the twisted memories it brought up. Objectively, roasting human smells the same as a rack of spare ribs. His mouth watered as memories he’d kept buried for years welled up. One more reason to hate the Penitents.

This was a small group of five, surrounding the saltire they’d leaned against the building. This was the go-to device of torture. As symbolic as the cross of Calvary, but with the mobility of being easily assembled and broken down with nothing but a few lashings and the support of a tree or vacant building. Under normal circumstances, he’d hunt the Penitents down, and coup de grace the sacrificiant. But, he was finally at the end of a project lasting several months. There was too much at stake in keeping to the plan he’d hatched six months ago. He couldn’t afford to shoot and move and be redirected from the lab. The sacrificiant had ceased screaming sometime around midnight. With little left to amuse them, they’d move out soon enough.

He kept thinking of spare ribs. He’d eaten nothing but ration packs for a week. They had everything the body needs, but nothing for the soul and spirit.

“Humph, soul and spirit? You are starting to sound like the Penitents.”

Wordlessly, the Penitents began breaking camp. The spent body of the sacrificiant was tumbled to the ground without further ceremony. The saltire was stowed. They walked away single-file. In the 25 years since The Fall, they had become the most prominent form of quasi-governance around, he’d never understood how they communicated before moving. It’s like they just knew when the deed was done and fell into step. It was an almost military-like operation. Maybe one day he’d beat the answer out of one of them.

He waited a good 15 minutes after they’d gone over the crest of the hill. He was too far along on the project to leave anything to chance. Once he knew no Penitents lingered, he made his way to the stairwell avoiding eye contact with the mirror at the end of the corridor.

He came out on the third floor into a dining hall area. Anything edible had long been looted, but he was looking for aluminum foil, a lot of it.

“Michelle, my belle, something French, I don’t know the words to the song, but I’m singing along. I love you, I love you, I love you …”

He’d had the chorus of the old Beatles song stuck in his head all morning and took the chance to sing it out loud, laughing at the absurdity. Today would have been his 76th wedding anniversary. He’d proposed to his Michelle with that same dumb line about not knowing the words to the song. She’d called him a dope and accepted the proposal.

The public housing facilities had been revolutionized in the automated socialism movement in the years before The Fall. With increasing automation and many service jobs relegated to a high-speed internet connection, it was easier to keep people at home. State-of-the-art cafeterias and recreational facilities were developed to be housed within each project. Everything, or almost everything that was needed could be had with just a few steps. The secondary benefit is that with people less likely to leave their own neighborhoods, they were less likely to see what went on in other parts of the country. Compartmentalized and tribalized, people were kept in check out of fear of each other. It worked for a time.

Aluminum foil, a good conductor and malleable. There should be a few large rolls of it in the cafeteria. It’s not something that the average plunderer would be out and about for, so with any luck one or two of the cafeterias in the blocks of public housing before him would provide what he needed.

He found the aluminum foil in a looted storeroom behind buckets of cooking oil.

“Rapeseed … It’s rapeseed oil,” he muttered

He’d met Michelle in an organic grocery store while trying to find grapeseed oil.

“That’s what the recipe calls for.”

“Grape seed or rapeseed?”

“Are you joking?”

“Rapeseed oil is commonly known as canola oil. There is no such thing as a “canola.” That’s just an acronym for like, the Canadian Oil Company or something.”

“Well, the recipe calls for Grape seed, not rapeseed.”

“Well, we have both. I just wanted to check.”

Thus, was her habit of random bits of information awkwardly inserted in a conversation. He’d liked that about her. She was his misanthrope. The first several years had been scandalously delightful, he at a constant youthful vigor, she, aging into a sexual peak. They’d tried and failed to have children. He never knew if that failure is what bothered her most or the fact that the man she loved wouldn’t grow old with her. She was dead before he thought to ask.

They lasted 19 years together before she blew her brains out, a week after he pinned on his first star as a brigadier general. Seven miscarriages, menopause, and the knowledge that your husband is unable to age are bound to send the most reasonable person over the edge.

He’d have to remember the cooking oil location, a good calorie source if it wasn’t rancid. And, a good fuel source otherwise. He carried the roll of aluminum foil down the stairwell and into the courtyard, and past the now fly-covered corpse of the sacrificiant. He donned a ghillie suit that he’d hidden in the burnt-out shell of a Volkswagen bus and began the long walk back to his lab. One more bit of material in possession. He would be ready in a few weeks.

Five days later, Obidiah flashed awake from his dreamless sleep. The scientists who had studied him after the implantations had theorized that dreams were actually a way to heal the mind—that the mind used dream cycles as a way of shuffling mental paperwork and filing things that were out of place. But, he no longer needed dreams. With things being repaired at the chromosomal level, he didn’t get brain-fatigue in the same manner as a normal person. There were occasional flashes of dreamscape after the most stressful of events, but they were so fleeting that they were not part of a coherent sequence of a typical dreamer who wakes up with a story to tell.

The lack of dreams was perhaps the least obvious oddity about him. He didn’t get sick. He didn’t scar. He didn’t age. Other than blunt trauma to the head or complete bleed out before giving the body time to regenerate, he really couldn’t be injured or die.

After gene therapy created the pathway for eliminating cancer, doctors started looking at other possible treatments for Alzheimer’s, autoimmune diseases, and other illnesses. The military got involved as part of the Chromosomal Hybrid Implant Program, an effort to make soldiers better by eliminating human error from the equation while still retaining the flexibility of the human mind in the fog of war.

He’d been in that first top-secret briefing when the Army Surgeon General gave a lecture that would militarize gene therapy.

“We see so many diseases being cured by the revolution of gene therapy. At birth, we can identify the problems a child will have, remedy them with gene therapy an allow a child to grow up free of cancer, autoimmune diseases, and thousands of other disorders that we once accepted as the fate of being human. If we can tweak the genes to prevent disease, can we also tweak the genes to reverse non-pathological processes?”

Obidiah was asked to attend the briefing for a variety of reasons. Obviously, his clearance helped, but he’d also been at the forefront of the movement of implants by private companies to make life more efficient. In addition to great leaps in medicine, the first half of the 21st Century had been a boon for technological solutions to every-day problems. By 2020, they’d ironed out credit card payments with a chip in the wrist that passed over a scanner. As a scatter-brained person always losing his wallet, Obidiah had said, “You mean I never have to carry a wallet again? Where do I sign up?”

Apple had been on the forefront of the movement, partnering with other corporations to make the synced technology that did things like implanting key fobs in the hip to allow people to unlock and start their car with no physical key in their hand. The economic depression that came in the early 30s saw Apple buying up defunct companies such as Fitbit, and leveraging their market share to change the way we consume.

The advertising slogan was “There’s a CHIP for that,” recycling their trademarked “app for that” slogan from the previous decades.

Obidiah was about as chipped-up as one could be, so he was invited to the briefing along with 130 other recruits straight out of Basic Training.

“The modern warrior must be more than just a fighter. We demand physical prowess, but also a knowledge of military history, tactics, a mastery of the spoken word. In short, we demand that you be superhuman.”

Based on the name of the briefing, Obidiah thought CHIPs was going to be an attempt at some sort of human-machine interface that allowed the brain to be accessed like a computer. It was something far less complicated but far more interesting.

“By the time the modern warrior has attained the level of knowledge requisite to be the super soldier we need, age has begun to take its toll. If we can freeze your age in time and grant you the ability to learn and study the military arts, then we create a soldier that can have the wisdom of an 80-year-old and the vigor of a 25-year-old. Based on research on age and the cure for the rare but fatal disorder of progeria, we have a way to eliminate the aging process.”

Want immortality? There’s a CHIP for that.

Obidiah was one of 93 chosen for the initial phase. Each had a series of implants in their bone marrow that worked in tandem to create a regenerative quality to the blood. Suddenly the body took minutes to heal instead of days or weeks. He winced at the memory of being a human pin cushion as doctors would slice his skin with a scalpel to show the generals how it mended nearly instantly. He would not age beyond his 26-year-old body.

It was with this 26-year-old vigor that he woke underneath a bridge along the remnants of an old paved road on the outskirts of what had once been Council Bluffs, Iowa. He’d run the 55 miles from his lab outside of the old capitol and swum across the Missouri River to Council Bluffs at night to avoid sentries from a fiefdom that had sprung up in recent months. He had personal knowledge of an RC-17 that had gone down just east of the river a few decades prior. He needed the wire. Recon jets were known for miles and miles of high-quality copper wire. He’d tried finding what he needed elsewhere, but he could never find the right lengths to suit his purposes. He had taken plenty of bits of copper wire from old alternators, but the surge of electricity he needed might blow apart a crudely spliced coil. He might have melted it all down and used in a cable making machine, but he had had no luck in finding a cable maker and did not have the tools to build his own.

“I’m no god,” he said aloud.

The combination of eternal youth and time to learn everything lent a certain supernatural quality to the 93. Some had referred to them as demi-gods for the seemingly infinite knowledge they possessed. It was a moniker that fit. At the time of the development of CHIPs, organized religion had been becoming more and more quaint. It rebounded with a fervor later, but at the time, science had fulfilled virtually every need. God was dead, and science had replaced her as a hybrid of man and science. He was as much a demigod as Heracles and Achilles.

For the first two decades, he’d been enlivened at the prospect of collecting knowledge. The army sent him to any possibly relevant courses of study. He would not attain rank while studying, but upon returning to garrison service, he would be applied as the military saw fit. He’d lost count of the number of bachelor’s degrees and certificate programs he’d knocked out. Small Engine Repair, Electronics, Engineering, military tactical schools, etc. He had the knowledge of ten men. He commanded men like no other, compliments of a Ph.D. in the Philosophy of Warfare.

He also would not advance beyond Brigadier General. Looking young for his age had not been an issue through the rank of Colonel. The military always had a Dorian Gray effect on its members, aging them on the inside while the exterior remained supple far longer than the civilian population, but even Colonels start to show wisps of gray about the temples and crow’s feet here and there. He was a Brigadier General with the body of a Captain and slowly he realized that he just could not command the respect he needed to do the job. He and the other “child generals” as they were dismissively called were scheduled to have the implants removed in order to restart the aging process, but it seemed they could never find the budget to undo what had been done. In fact, it was programs like CHIPs that eventually bankrupted the United States government and collapsed the entire country on itself.

As what tends to happen in declining nations, everyone blamed the intellectuals, including the scientists who might have figured out how to help him. The Penitents had increasingly grown in power, creating re-education programs for scientists, lawyers, bankers, and others viewed as causing the Depression. Some were not executed outright and sent to labor camps but they ended up starving anyway. After 20 years, the purge was still continuing with the Penitents ranging through the countryside rounding up what they perceived to be the sinners of capitalism, like that poor bastard a they’d burned alive few weeks ago in the public housing facility.

The 93 scattered during the collapse, but rumors of them persisted. Penitent leadership simultaneously denied that their god would permit such blasphemy and also issued bounties on the head of anyone proven to be unaged. After one of the 93 was hunted down and tortured to expose the others, the proof of their existence had been confirmed and they were added to the anti-science cleansing campaign. Of course, the child generals had a distinct advantage with decades of strategic training and most managed to eke out an ascetic guerilla existence against untrained and undisciplined Penitents. Some of the 93 just committed suicide to make an end of things. They healed rapidly, but something like a live grenade strapped to the throat was sufficient. He had heard of one controlling a fiefdom and actually bringing back a certain level of order to things. He knew that most that survived were likely planning on the same idea. Ride out the economic downturn and come out the other side as near immortals, ready to rule. Obidiah just wanted a chance at life, to age naturally, to die, unfettered by the device embedded in his marrow. The RC-17 was a waypoint on that path. He’d search for it in the morning. It was time to sleep.

Obidiah convulsed with the sudden shock of waking up again at 0645. Dreamless.

It had been three days since returning from the RC-17 wreckage. He’d taken two days finding it. A few decades of detritus had been built up around it and he’d had to dig to find an access point through the torn fuselage. He’d taken another day to find a strand of copper cable that hadn’t fused with its neighbors during the fire upon impact. It needed to be a single strand, malleable enough to wrap around a nonconductor.

The wire needed to be cleaned well, so he made another visit to a kitchen of the public housing complex in search of some sort of abrasive material and preferably soap of some sort. Steel wool had all rusted into nothing, but the little green pad made of plastic would work. The delicate tugging and scrubbing of 150 feet of wire and removing the charred plastic and decades of tarnish had taken more than a day.

The meticulous work was cathartic. He’d always enjoyed the slow methodical pace of sanding down a deck, painting a fence. It was his Zen. While he’d hope to finish the project soon, there was ultimately no rush. He was happy to take his time with the wire.

“Michelle, my belle, something French, I don’t know the words to the song, but I’m singing along. I love you, I love you, I love you …”

He’d never gotten an answer from the scientists on the repeated miscarriages. Gene therapy had made miscarriage virtually non-existent. The few members of the 93 that tried to procreate were the first cases in several years. On paper, he and Michelle were both healthy. He fully believed that his implants affected his sperm and that at some point the embryo just ceased to grow in the womb. The technology that allowed him to stay ageless prevented a child from coming to term.

Of course, Michelle blamed him. He’d volunteered for the experiment. He blamed himself. He had to. There is something unrecoverable in your psyche when you are mentioned in a suicide note.

Once it the wire was ready, he would wrap it around a glass tube he’d created from popping the end of a large beaker. He couldn’t remember why the nonconductive materials needed to be hollow. It was just one of those things he knew from a physics lab decades prior.

Popping off the end had actually been fun. He’d always had a little bit of a pyro streak in him, and after carefully wrapping some old yarn around the bottom of the beaker, just above where it curved upward, he soaked the yarn in acetone. Lighting that and letting it soften the glass for a few moments, he was able to plunge it into a vat of cold water and the bottom came right off.

After cleaning the wire, he took the rest of the day to read. It was one of the few pleasures of the life he led, He had an infinite amount of time to peruse the world’s remaining finite amount of literature. He had a few books in what had once been a female dormitory at the Lincoln campus of what had once been the University of Nebraska. That was his base of operations for the whole project. He was able to pop out of the sewers into a courtyard with his lab in one direction and a safe place to bed down in the other direction.

He called it a lab, but it had once been a student recreation area. What attracted him was the music room which had enough soundproofing to mask the noise the gasoline-powered generator he’d be using at the end of this project.

He couldn’t risk sleeping in the same area he worked. Should the Penitents arrive and find him in the lab, they would destroy everything. He spent as little time there as possible, gathering supplies together, storing them in a manner that they would not likely be found. If he had to flee, he could flee knowing that his work would be left alone for when he returned a few months later.

The courtyard was the site of a burnt pile of debris. Penitents had ransacked most college campuses early on in search of “liberal sin.” Their evidence was in the remnants of a bonfire outside the rec area—twisted heaps of musical instruments amid charred pages of “fiction smut.” Fiction smut was a catch-all for whatever Penitents didn’t like at the moment. Pornography was obvious, but for every now and then he would hear of a new edict pronouncing some bit of literature as fiction smut. He could find no rationalization as to why “A Tale of Two Cities” was on the list, but he could see a half-burned cover in the ashes. Truly, most Penitents burned all the books they could find, just to be safe. It was more efficient that way. This campus had been pretty well worked over by the Penitents, so they didn’t come back often and his work was safe.

In the girls’ dormitory he was working his way through The Complete Works of Leo Tolstoy. The girls’ dorm wasn’t a fetish. He’d just ended up there in search of scented candles that provided some light to read by. Of course, he only used candles during the long winter months. Hopefully, the scent of cinnamon mocha wouldn’t waft out of the building and attract unwanted attention.

Now it was summer and the sun set late in the evening. He could sit in the hallway and read in the ambient light that flooded in from other rooms.

He had a surprising choice of literature as one of the few people left with the desire to read it. The war on books had not destroyed everything, and one could still find literature here and there like the old give-a-book take-a-book system he’d seen in USOs during his military campaigns.

“Ransacking the forgotten office of a professor for batteries? Feel free to take a dog-eared copy of Practical Physics and leave behind Lolita. He’d managed to read through many of the classics in the 10 years since The Fall. He’d also worked his way through a share of pulp fiction and moldering magazines. A few weeks earlier he’d come across a nearly mint condition stash of Zunder Girls from the middle of the 21st Century. Such things had trade value.

One curse of his eternal youth was having the libido of a 26-year-old. After 82 years, it was unpleasant. Sex was an impossibility, and masturbation became a must just to keep sane. Small blessings in the sense that at least he didn’t have the libido of a 16-year-old. Masturbation then had been on the most banal of pretenses. Somehow a North American Hunting Magazine feature on elk in rut could stir the loins, and don’t forget the time he’d been caught with his mother’s Good Housekeeping with a 40-year-old Selena Gomez on the cover.

“The Queen of Sync-Swing Opens Up on Faith, Family, and Fun.”

He’d been in the backseat of the family’s self-driving van. His mother had opened the sliding door without any warning stared him down and saying nothing except, “Keep it. Under no circumstances do I want that magazine back.”

She never brought it up again; something he privately thanked her for. She was dead now and had been for as long as he could remember. Everyone was dead. Agelessness was lonely. Before reading he paged through the stash of magazines wanting something new to add to his overused mental images of long-dead women over whom he’d once fantasized. He fell asleep before picking up Tolstoy.

Flash of light, no dreams, 0645, well rested, no soreness, another day.

It was capacitor time. A capacitor wasn’t hard to build—child’s play. Literally, he’d seen kits as a boy that allowed you to charge up a wand by rubbing it on the carpet and then zap a friend with a few volts. The original Leyden Jar had been something like a nail in a glass of water (with enough capacitance to kill its creator). Six Capacitors in parallel with sufficient voltage and microfarads for his project was a little more technical, but still not much more than complicated than a child’s toy.

He lined six five-gallon buckets with the aluminum foil, and placed the lids on them with conducting rods facing up with wires pre-attached. That should be sufficient. He’d learned most of what he needed during one of his stints as an engineering student.

The coil of wire around the beaker he’d completed a few days earlier was already connected to the light switch that separated the capacitor from the coil. His soldering wasn’t a work of art, but it would do.

Everything he needed was now in the lab, stashed where it would not draw attention.

He checked in a back room for the small tin of gasoline. He’d traded a sizable stash of ammunition for that half-liter, but it was all he needed. Refineries were nearly nonexistent at this point and the piss-yellow fuel was more contaminants than gasoline. It was worth its weight in fiction smut. A few clean-ish rags layered in a colander he’d taken from the kitchen were sufficient to clear out most of the debris. A few tablespoons of the highly distilled brew he made himself would take care of any water while not disrupting the octane too much to prevent it from starting. He’d done this enough to know what worked. He’d taken a six-month small engine repair course in order to maintain the 2-cycle motors they’d used in counter-guerilla warfare during the Burma campaign. Good to see that the training would still be put to use, 30 years after the disastrous results of that war.

He went back to the dormitory. He was anxious about tomorrow. He could probably take care of things now, but he wanted to take a few more minutes on reviewing everything. If only part of his device worked, he’d be set back months. After 82 years, he could wait one more day.

The same flash of light, the same jolt, the same instant consciousness. Every. Single. Day.

But today would be the last day.

He eye-balled everything. The generator was connected to an old muffler polished until it gleamed. That served as the end of a spark gap. From there the muffler was connected to the capacitor bank. He opened up the lid of each capacitor to make sure that the wand reached all the way to the packed foil at the bottom. It did. The wires soldered to and from the switch were secure. The coil was a work of art, the only part of the project that looked like it would work. From the coil, he wrapped back to another muffler.

It was a ramshackle device conjured from salvage and charged with the filtered gas and imagination … However, it was an electromagnetic pulse generator. It would work. He knew it would work. There was no reason to even test it out. He stood between the spark gap and the coil. He didn’t know the exact range of the pulse, so he didn’t want to be too far away when he turned it on. He silently counted down from 10, the memories of 108 years of memories flashing in the back of his eyes. He would not remember toggling the switch. There was only a searing flash of light before falling unconscious.

His head was pounding when he woke up and he was sore from the cold tile floor he’d been laying on. Surely, soreness was a good sign. He hadn’t been sore from anything in 82 years.

His watch was dead. He had no idea how long he’d been laid out on the floor, but based on the sun angle, it had to be late afternoon.

He was thirsty.

“Damn this headache is killing me.”

He pulled out a penknife and cut a slit along his palm. The blood welled up and dripped down onto his boots. He watched it drip for a few minutes with fascination.

“That should have already healed.”

“I should have made a smaller cut.”

If he could be injured, then he could age too. The EMP had taken out the devices inside him.

“Free to age, free to live, free to die.”

He went for a walk.

Obidiah lay in his hide, waiting for the first vestiges of dawn to appear. Waking up early or sleeping in hadn’t been something he’d considered when building the EMP. The other circuitry, including his alarm clock had been fried. The tattered copy of The Complete Works of Leo Tolstoy lay beside his cot. He’d yet to finish it.

The world hadn’t gotten any better in the two years since he completed the EMP. He still dodged Penitents. He still dodged memories of those he’d left behind decades before. But he didn’t avoid looking in mirrors anymore. In fact, he relished looking at a few crow’s feet he’d developed.

“Old man, what are you looking at? Pretty wrinkled for 28, or am I 110 now?”

He glared at the first traces of a receding hairline. All the men on both sides of his family had been bald by 30. He’d staved off that aging the same way he’d staved off all other aging. Baldness now was not much of a price to pay.

“Male pattern baldness? Maybe there’s a CHIP for that?”